I was going behind the house to fill the deer feeder when I came across this six-foot Black Rat Snake (Elaphe obsoleta obsoleta). I followed it along for a while and got some closer photographs.

This picture of the snake’s head shows its characteristic white chin. The round shape of its pupil is also evident. This should cause you to relax if you are worried that it might be venomous. Of the venomous snakes native to the United States, only the Coral Snake (Micrurus sp.) has a round pupil, and Coral Snakes have a very distinctive color pattern of red, black, and white bands around their body. Rattlesnakes (Crotalus sp., Sistrurus sp.), Copperheads (Agkistrodon contortrix), and Cottonmouths (Agkistrodon piscivorus) all have vertically-elongated, cat-like pupils.

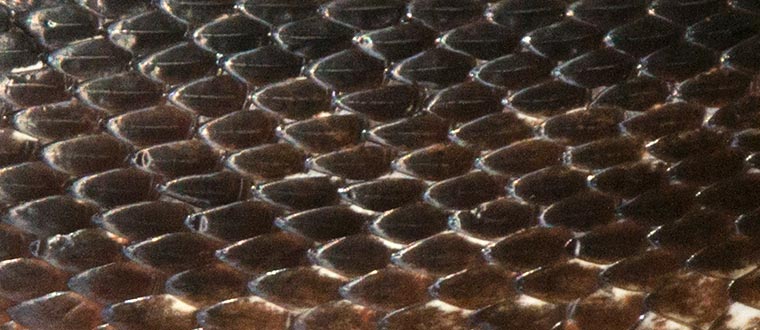

A close up of the snake’s skin shows the precise pattern of its scales. This side view shows that the scales toward this animal’s back have keels, slight ridges on the scale’s surface. Snakes have to use a lot of energy to move about, and one of the main functions of snake scales is to reduce friction. Snake scales are made of keratin, as are human fingernails and hair.

Snakes are hatched (or born) with a fixed number of scales. The scales get larger as the snake grows and may change their shape, but the number does not change.

Doubtless, most of you have seen shed snake skins that the former possessor has vacated, and is now enjoying a fresh new skin that was formed under the old one. This process (called molting or shedding) helps to shed external parasites and replaces damaged scales. Since a snake’s skin is rather inflexible, shedding an old skin is necessary for growth. Although the scales seem to be individual units, they form, in fact, a continuous layer with the epidermis. This can be seen if you examine a shed snake skin closely.