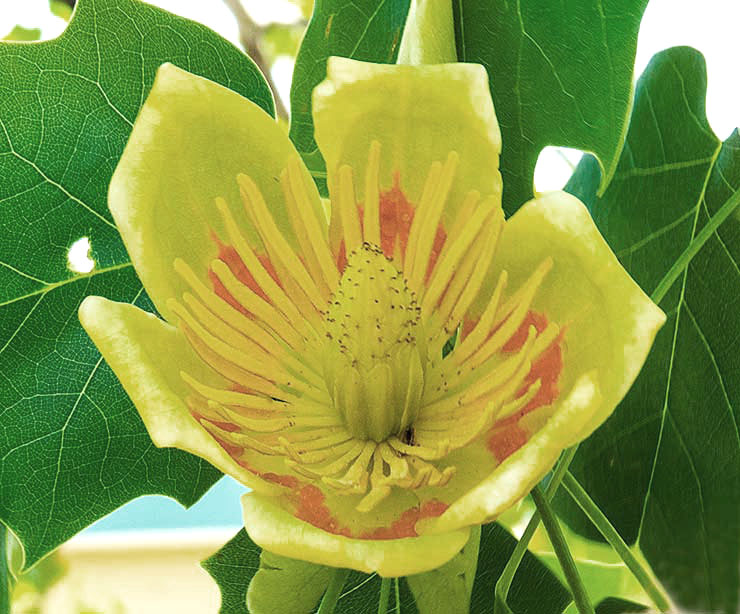

It is clear why Liriodendron tulipfera is called Tuliptree when you see the flowers. Another name for this common tree is Yellow Poplar, because freshly cut wood is a light yellow-green in color and the leaves flutter in the wind as do the leaves of true Poplars. Each flower has three sepals, which are folded down from the flower in the photograph above, and six petals. Many stamens are arranged in a whorl just inside the petals. The central column will form a cone-like structure with 60 or more winged seeds.

Mature Tuliptrees have tall columnar trunks that can be quite massive. They are the among the largest trees found east of the Mississippi with heights reaching almost 200 feet and trunk diameters of up to 10 feet. Where we grew up on Southern Indiana many old barns were supported by massive internal beams of Tuliptree wood. The wood is, however, relatively soft and not suitable for external exposure. It is also not prized as firewood, because it burns very quickly and does not produce much heat. Its fine grain and large trunk size enabled Native Americans to use Tuliptree trunks for the construction of dugout canoes. Tuliptree flowers are also an important honey plant in the Eastern U.S.

Tuliptrees are not, of course, closely related to tulips, the similarity in flowers is coincidental. Nor are they closely related to true Poplars. Tuliptrees are in the Magnolia family. There are two closely related species: Liriodendron tulipifera, our North American species, and L. chinense, native to Vietnam and China. The two species can be hybridized. It may seem strange for two closely-related species to be so widely separated geographically. However, fossils show that Liriodendron had a circumpolar northern distribution at an earlier time. Large-scale glaciation with accompanying periods of aridity, wiped out Liriodendron in Europe and much of Asia producing the present disjunct distribution.